I’ve been working on a new project about the history of Faneuil Hall and I came across an exchange in a 1765 Boston newspaper that caught me off guard in the best possible way.

First, you should know that the 1760s were a complicated period in New England history: the French and Indian War concluded in 1763 and brought with it all sorts of questions about power and identity, Bostonians became increasingly agitated by British schemes to pay off war debts and exert political authority, an economic depression settled in, and the relationship between religion and science continued to evolve and lead to new ideas and challenge old ones (as expressed through the Great Awakening and Enlightenment movements, respectively).[1]

In addition to stories from home, other colonies, and abroad, Boston newspapers ran ads for town elections, divisions and subdivisions of land parcels, and commodities like duck canvas, tea, turpentine, hemp, wheat, nails, horses, clothing, and enslaved people.[2]

So, while Boston townspeople were informed of national and international events and were exposed to different philosophies on logic and reason, people also went about the process of living their everyday lives.

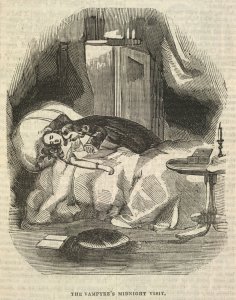

Which brings me to April 1, 1765. The Boston Evening-Post that day ran a curious front-page story titled “The surprising account of those spectres called vampyres.”

That’s right. Vampires.

This isn’t just a blurb, either. It’s a full-length column. The printers gave it top billing over a piece publicizing a generous donation that Thomas Hancock (John Hancock’s rich uncle) bequeathed the Town of Boston when he died.[3] Even a reprint of a speech by King George III to Parliament was vanquished to page two.

“These vampyres are supposed to be bodies of deceased persons animated by evil spirits, which come out of the graves in the night time, suck the blood of many of the living, and thereby destroy them,” the piece begins. “Such a notion will probably be look’d upon as fabulous; but it is related and maintained by authors of great authority.”

The printers go on to quote at length a person called M. J. Henry Zopsius, one of the so-called authors of great authority. They even cite various historical vampire occurrences from overseas (mostly Eastern and Central Europe) and the Bible. Zopsius’s description of vampires isn’t all that different from today’s pop culture representations.

It was a sensationalist story meant to draw eyeballs (it certainly drew mine) and generate sales revenue. New England historian J. L. Bell also suggests that the story was lifted from the January 21 issue of the Connecticut Courant. (The quote from Zopsius, Bell adds, was pulled right from the anonymously written The Travels of three English Gentlemen, from Venice to Hamburgh, being the grand Tour of Germany, in the Year 1734.)

It compelled a pretty harsh rebuke aimed right at the printers, Thomas and John Fleet.

The respondent’s salvo opens with an opinion on journalistic ethics and responsibility, even acknowledging that on slow news days “retailers of public intelligence and speculation” can make up stories so long as those stories offer the reader some kind of moral or epistemological lesson.

But for the respondent, the vampire story from April 1 was a match in the powder barrel.

“Most certainly, neither the publishers themselves, nor any sober man and good christian, can believe there is one word of truth, in all that long, surprising, and terrific account exhibited in the aforesaid paper,” they wrote. “Besides, how ridiculous as well as impious must it be, to suppose that the Supreme Being would commit the keys of death to infernal spirits and demons, and suffer them to drag dead bodies of men from their graves, and make them instruments to destroy the living?”

“For my own part, I can as soon give credence to the most fabulous stories of witches and spectres, of demons and goblins stalking by moon-light; or believe the whole phenomena of the Salem witchcraft; the incubusses, the succubusses, the preternatural teats; with all the trumpery and wonders of the invisible world: Or the scene of witchcraft open’d at Woodstock, a few years ago, when 132 stones of different sizes, were said to be thrown into a room (close shut up) by the agency of infernal spirits;——I say, I can as soon give credit to all this, as to the surprising account of the sanguinary vampyres.”

I found this back and forth to be rather amusing. After reading petitions, pamphlets, and scholarly analyses on British taxation in Boston, it was funny to come across such spirited debate on such a silly subject. I mean, here we are in colonial Boston where the ideals of the American Revolution are crystallizing, where men are extrapolating on their natural and political rights and liberties, where the public is mobilizing into collective (and violent) action, and all the while we’re debating the merits of vampire tales?

I’d like to think that the vampire article was supposed to be a political metaphor for the situation brewing in Boston but it almost certainly was not. There were no allusions to such, nor any clarifying follow-ups by the printers; there was only the rebuttal by a very self-assured and very offended vampire skeptic.

The article and response do, however, offer us some insight into the socio-cultural conditions of mid-18th century Boston. It shows the tension between the Great Awakening and the Enlightenment, between accepted folk traditions and fact-based scientific knowledge. That’s what we’re seeing play out here. It’s a reckoning of two complex and nuanced modes of thought, one where knowledge is grounded in established traditions and the other in logic and evidence.

It could also be an example of someone using the print media to vent their own frustrations. Perhaps the pointed response was a knee-jerk reaction to an article that struck a last nerve, today’s equivalent to firing off angry emails or trolling social media feeds when we’re exposed to something we find disagreeable. It’s a relatable feeling and would seem at least understandable given the political and economic stresses that weighed upon colonial Americans. It may have been like hitting the release valve to blow off steam.

I love how this commentary adds a human dimension to the historical narrative of Revolutionary Boston. Too often when we talk about the people and events of the American Revolution, we overemphasize the political, economic, and military aspects of the time. This vampire episode brings us back down to Earth. We can see things at ground level. It offers us a social perspective of a certain time and place: The Fleets are trying to make a buck, the respondent uses what today we’d call “common sense” to disprove ghost stories, and we witness what may be an example of colonial trolling or, in today’s parlance, “owning.” All of this is happening within the context of political unrest, economic recession, religious fervor of the Great Awakening, and scientific reasoning of the Enlightenment.

[1] As another example of the swirling forces of the Great Awakening and the Enlightenment, consider the column “Of the Weather,” published in The Boston Evening-Post in March 1765. The author explores how the weather affects peoples’ dispositions, correlating sunny days with virtuosity: “It is remarkable what sympathy there is between a humane spirit and the weather… I know several, who, with the assistance of the sun, are very honest fellows, but in a shower of rain, are as great knaves as any in the alley.” The author melds together the science of meteorology and morality largely informed by religion.

[2] It was not unusual for Boston newspapers to advertise enslaved people for sale among ads for other goods. For example, in March 1765, The Boston-Gazette and Country Journal carried an ad reading “TO BE SOLD, (For no Fault;) A Likely, Strong Negro GIRL, about 16 years of Age, that has been used to House Work: Inquire of Edes & Gill.”

[3] That piece reads in part, “it is further Voted That the Name of HANCOCK be recorded and enrolled among those of FANEUIL, and other worthy Benefactors of this City…” More on this in another post, hopefully soon.

Very entertaining – you provide a window into real life Colonial Boston.

LikeLike

Well done Nick

LikeLike