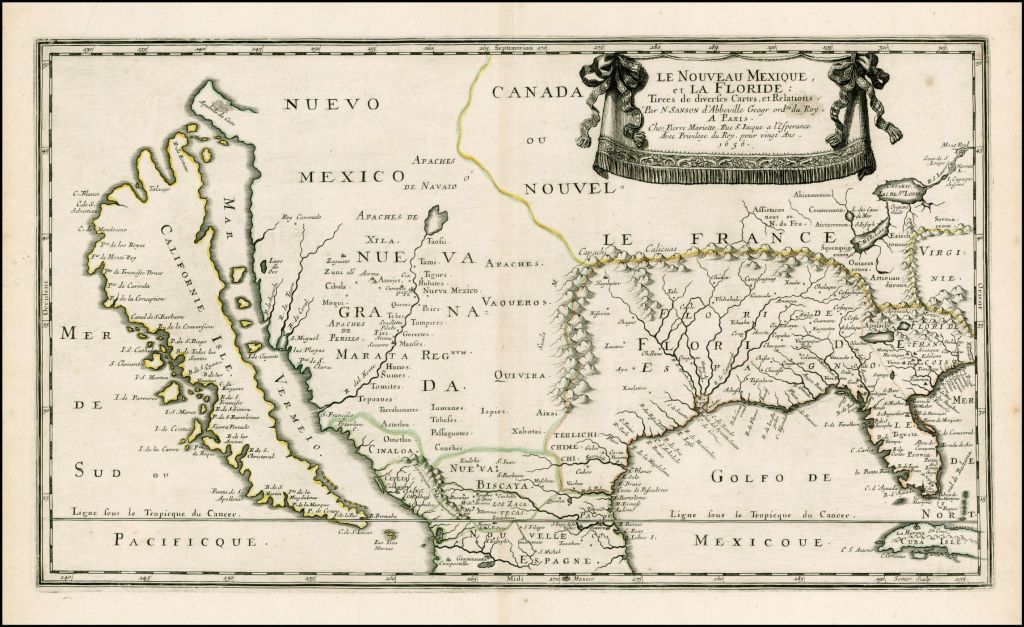

This map, called Le Nouveau Mexique et La Floride, is one of my documents. I came across it in a book called Maps of Texas and the Southwest, 1513–1900 when I did research on the Big Bend region of West Texas.

The Big Bend is named for the sweeping serpentine curve in the Rio Grande as it flows southeast from the mountains of Colorado to the Gulf of Mexico. It’s a major geographic feature in the US-Mexico borderlands and a place of deep historical significance. Today it is home to Big Bend National Park, one of the largest American national parks by land area and one of the least visited.[1]

According to this map, though, the Big Bend doesn’t exist.

French cartographer Nicolas Sanson d’Abbeville created this map in 1656. Remarkably, it depicts the Rio Grande as emptying into the Gulf of California, not the Gulf of Mexico. It’s the wrong direction and consequently eliminates the Big Bend from the landscape entirely.[2]

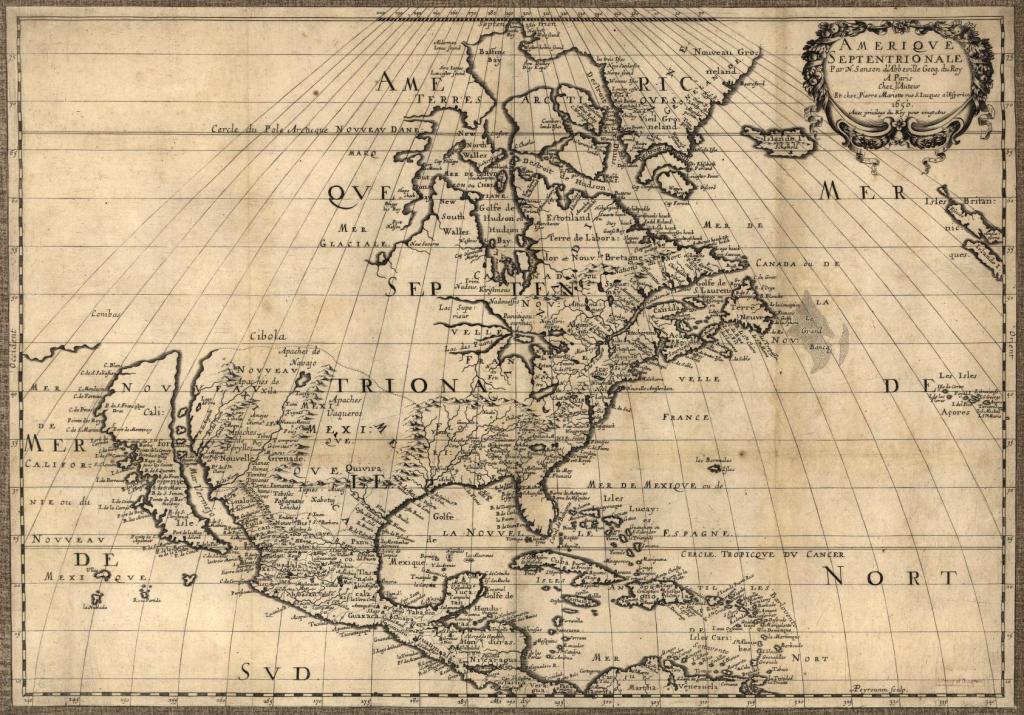

This wasn’t the first time Sanson d’Abbeville charted the Rio Grande this way. His 1650 Amérique Septentrionale likewise misrepresents the Rio Grande. The overall scope of that map is much larger. Sanson d’Abbeville really embellished the terrain. He included rivers, lakes, mountains, and territory occupied by Indigenous tribes and nations. He also outlined much of the continental coastline and the result is not unrecognizable to us today. It demonstrates Sanson d’Abbeville’s idea of the North American Continent, whereas Le Nouveau Mexique et La Floride focuses on today’s American Southwest, California, and Gulf Coast using the same artistic style.[3]

But he didn’t really know what he was talking about.

This was not uncommon. Sanson d’Abbeville had no first-hand knowledge of the actual landscape. European non-Spanish cartographers in the 16th–18th centuries created maps of today’s American West largely from information gleaned from each other. That’s because Spanish maps were state secrets. They didn’t want other imperial European powers encroaching on the land they conquered or the resources they appropriated. Many colonial maps of North America circulated around Europe during this time were of English, French, Italian, and Dutch origin.

Le Nouveau Mexique et La Floride portrays an imagined landscape, what Sanson d’Abbeville thought the American Southwest looked like. It’s not a geospatially accurate representation. While yes, it does include rivers, lakes, mountains, and Indigenous territories, most of it is misconstrued: in the West, not only is the Big Bend nonexistent but so too is the Pacific Northwest; California is an island; and semi-sedentary and quasi-nomadic Indigenous peoples appear to inhabit fixed geographic locations — in the East, four major rivers lie parallel at the center the Mississippi watershed instead of smaller tributaries that feed the larger Mississippi River; mountains ring around the north of the Mississippi watershed; and the distorted scale of the whole map puts the Great Lakes (only two of them, by the way) next to Virginia.[4]

Just as important as what maps show is what they don’t show. Any time we look at a map, we see landscapes as filtered through the judgements, prejudices, and cultural context of the mapmaker. As such, maps are valuable tools for understanding power dynamics. The mapmaker includes what they think is important and excludes what they don’t. In this case, Sanson d’Abbeville prioritized aesthetics over accuracy, European visualizations over Indigenous. To his credit, he did attempt to display geographic elements with intuitive designs. His work became pivotal for European cartographic production because he pushed map production to become more a science than art. His method and style influenced European cartographers for the next hundred years.[5]

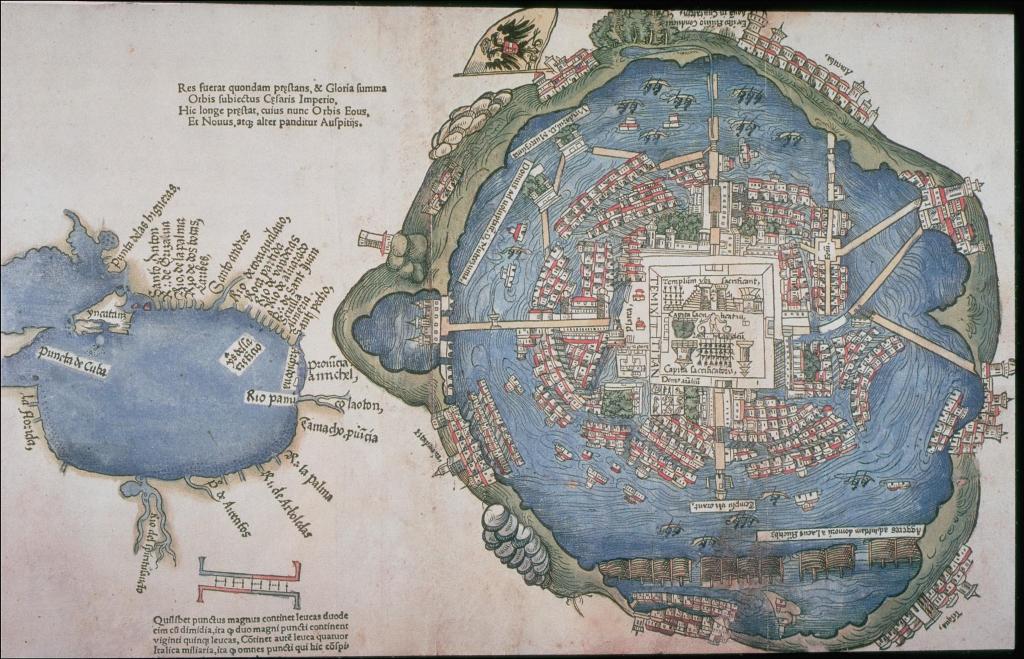

Now, let’s compare Sanson d’Abbeville’s substance with the mapping techniques of Indigenous peoples. For example, take what’s known as the Nuremberg Map of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital besieged and sacked by conquistador Hernán Cortés. Today we call it Mexico City.

Cortés dispatched this map back to Spain along with letters to the king after setting out for his conquest of Mexico in the early 1500s. Academics once assumed Cortés or his top lieutenants created the map but scholar Barbara Mundy argued it was a influenced both by the Aztecs and Spanish. She recognized that the map does possess some aspects of European cartographic design but its order and focus are Aztec.

Tenochtitlan did not sit in the center of a circular lake as shown in the map, but rather on an island chain within a system of lakes in a highland valley. At the city center we can see the temples, pyramids, and human sacrifices that correspond to Aztec interpretation of the cosmos. These details align with Aztec concepts of spirituality at the heart of a great empire bounded by a cyclical perception of time.

But we also cannot consider this map without placing it in the context of the Spanish conquest of Mexico. To justify his invasion of Mexico to the King of Spain, Cortés had to conjure a place inferior to Spanish power, alluring for Spanish enterprise, and captivating of Spanish imaginations. The map is a visual and tangible manifestation of this goal. We can see, then, how Indigenous map techniques, motivations, and socio-cultural context vastly differed between Amerindians and Europeans.[6]

As another example, consider the bands of Apache peoples who lived predominantly in today’s Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. As scholar Keith Basso documented in his fieldwork with the White Mountain Apache, maps for them were a sort of mental construct. They were manifested in stories, not committed to paper in two dimensions. They involved a place, a narrator, an audience of one or more, and tales steeped in “wisdom, notions of morality, politeness and tact in forms of spoken discourse, and certain conventional ways of imagining and interpreting the Apache tribal past.” This may be difficult for us to fathom today in a world of digitally rendered maps courtesy of ArcGIS and Google Maps, but we can begin to comprehend that Apache mental maps were not so much a tool for navigation or landscape representation as they were a function for teaching and learning the parameters of Apache culture and history.[7]

When I look at Le Nouveau Mexique et La Floride, I don’t just see a map that’s charming for both its beauty and its faults. I see a story. Because that’s what maps do, they tell stories. And this story is about more than the orientation of mountain ranges or which way the rivers flow. It’s about conquest. It’s about imperialism. It’s about whose culture is promulgated and whose is silenced, and who gets to make that decision.

[1] Of the 63 American national parks, Big Bend is the 14th largest national park by land area and 37th in annual visitors.

[2] The Spanish originally called the Rio Grande the Rio Bravo del Norte or sometimes just Rio del Norte or Rio Bravo. It wasn’t until the arrival of American settlers that the name Rio Grande stuck.

[3] What is that peninsula up in the Pacific Northwest, the one labeled Agubela de Cato? If I had to hazard a guess, it may be the Olympic Peninsula of Washington State or Vancouver Island, British Columbia

[4] The ring of mountains around the Mississippi Valley is labeled Suala Mountains. John Lederer, a German colonial explorer, published a narrative of his expeditions in the North Carolina Appalachians in 1669–1670. In it, he noted that the Suala, a western portion of Blue Ridge, were named by the Spanish. Sanson d’Abbeville obviously knew of the Suala Mountains, but it seems he didn’t know where to approximate the western slope.

[5] It’s not until the early 1700s that European maps started showing the Rio Grande flow into the Gulf of Mexico. And, using these five maps (one, two, three, four, five), you can see how geographic accuracy improved from the mid-1600s to mid-1700s but also the lasting aesthetic influence of Sanson d’Abbeville.

[6] Barbara E. Mundy is Professor and Professor Martha and Donald Robertson Chair in Latin American Art at Tulane University. Her “scholarship dwells in zones of contact between Native peoples and settler colonists as they forged new visual cultures in the Americas.”

[7] Keith Basso was a cultural anthropologist who conducted fieldwork with the White Mountain Apache tribe in Cibecue, Arizona for 30 years. He taught at the University of New Mexico, University of Arizona, and Yale University.